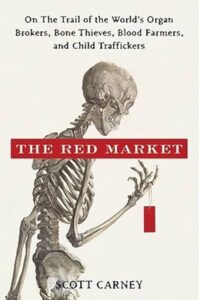

The Red Market by Scott Carney

Written by Ashley Kelmore, Posted in Reviews

Rating:

Rating:

2.5 Stars – a solid ‘fine.’

In a nutshell:

Investigative journalist Scott Carney explores the various ways humans sell bodies and body parts.

Best for:

Those interested in the ethics of these issues and who aren’t squeamish.

Lines(s) that stuck with me:

N/A

Why I chose it:

The audio book selection from my local library is ROUGH. Virtually none of the books on my TBR list are available, so I started scrolling non fiction and this seemed interesting. Also … medical things fascinate me, as does ethics.

Review:

How can you ethically procure a non-renewable resource? Or a resource that requires someone to literally give of their own flesh? And what about when that resource is needed to save a life? What if that resource isn’t actually needed, but people really want it?

Carney’s book explores a variety of scenarios where human anatomy is procured in ways that may be unethical, questioning both the black (or ‘red’) market approach as well as the legal routes for securing these resources. He looks at getting bodies and bones for anatomy studies, blood for surgery, eggs for surrogacy, kidneys for transplant, volunteer for drug trials, and even babies for adoption.

One critique that I think holds for this book is that in nearly every example (save, if I recall correctly, blood donation, which I’ll get to below), Carney really only explores the red markets of other countries, usually India, though sometimes China as well. For example, he (rightfully, I believe) explores the unethical nature of so many international adoptions, including situations where parents didn’t actually think they were relinquishing their children – and where US adoptive parents refuse to return those children. But he doesn’t explore the ethics of US domestic adoption. In fact, I think there is a real missed opportunity here to explore the actions of those who provide something that no one actually needs – a baby. This also goes for the section on egg harvesting and surrogacy.

Most of what else Carney explores one could argue is a necessity – blood for a surgery, or a kidney to stop needing dialysis, or, at a higher level, stem cells for research purposes. And the question becomes: if someone needs it, is it right that another person should be prevented from providing it if they are remunerated? And what is the cost of that to the seller/donor, and to society? How much is your kidney worth, and if you are possibly not able to feed your children, how low a price might someone offer?

I found the chapter on blood donation especially fascinating. A little over a decade ago I served on the junior board of the non-profit who manages blood collection (not the American Red Cross) in the city I used to live in. I also used to donate blood regularly (the UK makes you wait much longer between donations, so I can’t donate as regularly here) and platelets on occasion. I was shocked (not that shocked) to learn that in the 60s, corporations managed and paid for blood donations and then sold the blood to hospitals. When non-profits got involved, these corporations actually filed claims of an anti-trust nature, saying these non-profits seeking volunteers were preventing them from making profits, and for awhile US government agreed, fining these non-profits daily. Fucking WILD. Also, there was a whole thing where prisoners in Alabama were ‘donating’ blood, and that blood wasn’t screened, and was sold to Canada, leading to a lot of issues.

Carney argues that one of the best things we could do is require that all human body parts and resources have a name associated with their donation. Every pint of blood, every organ donation, every body. While some argue that privacy is the ethical choice, Carney argues that having a name will reduce the likelihood that someone is coerced to give their flesh and bone. While it wasn’t providing my name, as a blood donor they trialed a project where I would get a text when the blood I was donated was used, which was pretty cool, and probably an incentive for others to keep donating when they had the chance.

There’s much more in the book – the above are just the areas that really stood out to me. And as I said, there seems to be a real issue around the countries that Carney chose to focus on – India and China cannot be the only places participating in unethical human organ / blood / tissue procurement, and it feels weird that (as best as I can recall) Carney doesn’t really even pay lip service to the issues taking place in any of the other 200+ countries in the world.

Would I recommend it to its target audience:

Sure, but probably as an audio book as you could get the washing done at the same time., and with the caveat that there might be some bias in what the author has chosen to highlight.